The Dutch government has agreed to return thousands of fossils to Indonesia from a world-renowned collection, after a commission ruled they were removed in the colonial era “against the will of the people,” the education ministry announced on Friday.

The historically significant trove known as the Dubois Collection includes a piece of skull uncovered from the Solo River on the island of Java that is regarded as the first fossil evidence of Homo erectus, which is generally considered to be an ancestor of our species, Homo sapiens. The fossils are often referred to as “Java Man.”

The decision to return more than 28,000 fossils to Indonesia is the latest act of restitution by the Dutch government of art and artifacts taken — often by force — from countries around the world in colonial times.

The fossils were excavated in the late 19th century by Dutch anatomist and geologist Eugene Dubois, when present-day Indonesia was a colony of the Netherlands.

After extensive research, the Dutch Colonial Collections Committee concluded that “the circumstances under which the fossils were obtained means it is likely they were removed against the will of the people, resulting in an act of injustice against them.”

Fossils held spiritual and economic value for local people, who were coerced into revealing fossil sites.

Minister of Education, Culture and Science Gouke Moes sealed the agreement on Friday with his Indonesian counterpart Fadli Zon at the Naturalis museum in Leiden, where the collection is currently housed.

“The committee’s advice is based on extensive and thorough research,” Moes said in a statement. “We will apply the same level of thoroughness in working with Naturalis and our Indonesian partners to ensure the transfer proceeds smoothly. Indonesia and the Netherlands believe it is important for the collection to remain a source of scientific research.”

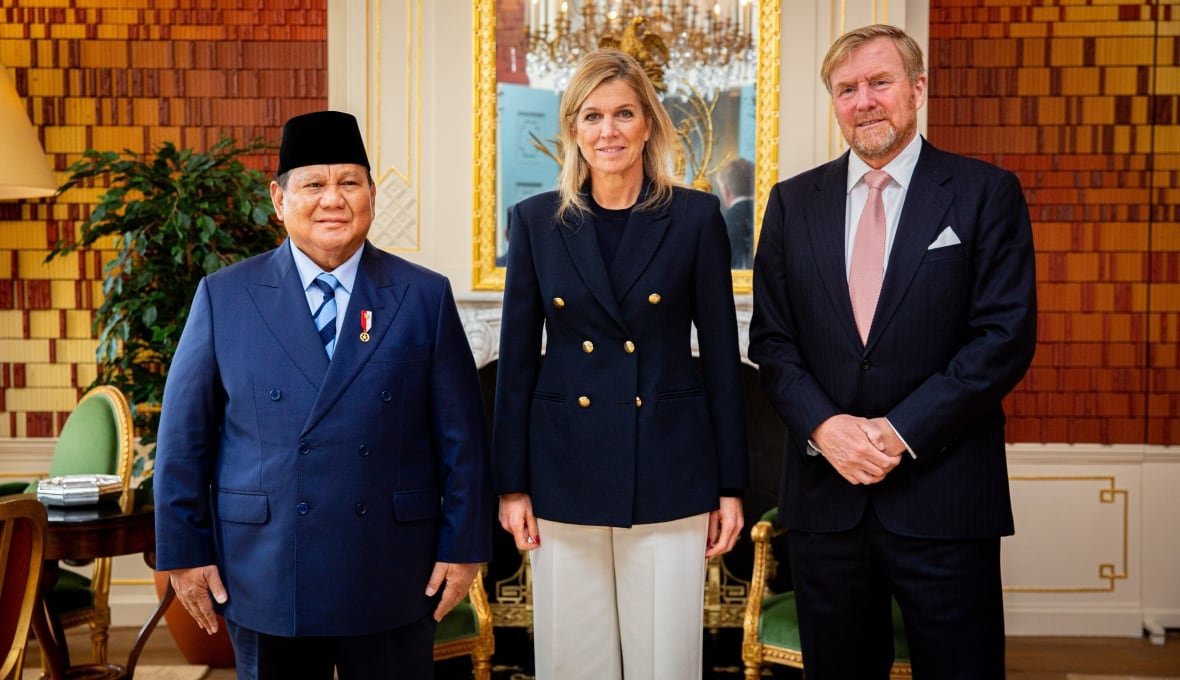

Also Friday, Indonesia’s President Prabowo Subianto met Dutch King Willem-Alexander and Queen Maxima at their palace in The Hague.

Homo erectus arose in Africa about two million years ago and spread widely there and in Asia, and possibly into Europe.

It reached Java more than 1.5 million years ago, and dating techniques suggest it died out at least 35,000 years before the arrival there of our own species, Homo sapiens.

Stolen artifacts go home

This isn’t the first time the Netherlands has returned artifacts or objects that were stolen during its colonial past. In 2023, it returned hundreds of objects to Indonesia and Sri Lanka, and returned more to Indonesia again in 2024, including four Hindu-Buddhist sculptures.

Some other Western nations are returning looted artifacts and other objects as part of a reckoning with their often brutal colonial histories. Earlier this month, Madagascar received three skulls of Indigenous warriors returned from France, including one believed to be of a king killed by French troops 128 years ago. The repatriation marked the first use of a 2023 French law regulating the return of human remains to its former colonies.

In recent years, a Berlin museum announced it was ready to return hundreds of human skulls from the former German colony of East Africa, and Belgium has returned a gold-capped tooth belonging to the slain Congolese independence hero Patrice Lumumba. France said it was also returning statues, royal thrones and sacred altars taken from the West African nation of Benin.

Although repatriation efforts have increased in Canada, there’s still no federal legislation facilitating repatriation from Canada’s museums.

Repatriation usually occurs on a case-by case basis in Canadian museums. The Royal Ontario Museum, Canada’s largest museum, returned possessions of a 19th-century Plains Cree chief to his descendants in 2023.

A government survey published in 2019 found there were roughly 6.7 million Indigenous cultural artifacts in Canadian museums and an estimated 2,500 ancestral remains.

Meanwhile, Indigenous groups within Canada have been fighting for the return of artifacts and human remains that were taken to Europe by colonizers.

The federal government reached an agreement with the National Museum of Scotland in 2019 to return the remains of a Beothuk husband and wife, whose graves were ransacked by a Scottish Canadian explorer in the 1820s. The same museum returned a memorial totem pole belonging to members of the Nisga’a Nation in northwestern British Columbia in 2023, after displaying it for nearly a century.