Project aims to study sun’s corona

Unless you’ve been living under a moon rock, you probably remember the total solar eclipse that happened last year.

Now scientists are trying to create a series of artificial solar eclipses — but you won’t need to whip out your eclipse glasses for these.

Last month, the European Space Agency (ESA) launched two satellites into orbit from India that will soon begin working together to create solar eclipses.

ESA said the eclipses will be visible to one of the satellites, but not to humans here on Earth.

The mission, called Proba-3, aims to help us better understand the sun’s outermost atmosphere, known as its corona — the thin ring of light that can be seen around the moon when it eclipses the sun.

How it will work

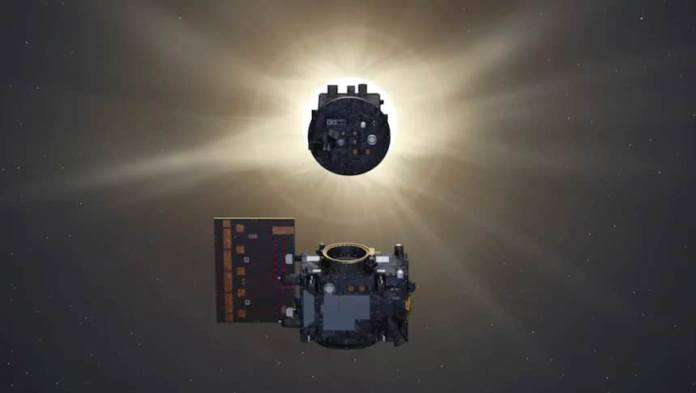

Once the two satellites are roughly 60,000 kilometres above Earth, ESA said, they will separate and lock into position 150 metres from one another.

One satellite will hover directly between the sun and the second satellite, which is equipped with a special type of telescope.

Each satellite is cube-shaped and less than 1.5 metres wide. One satellite will hold a circular disk which acts as an artificial moon, casting its shadow down to the other satellite. (Image credit: ESA)

When the second satellite faces the sun, it will see the sun eclipsed by the first satellite, and will only be able to see the corona.

Why they’re doing it

Scientists want to study the sun’s corona, but it’s almost always obscured by the bright light emitted by the sun’s surface.

The only time to view the corona clearly is during solar eclipses, but natural ones are rare and may only last a few minutes.

With this project, ESA is aiming to create two eclipses a week, for six hours at a time, over the next two years.

The primary goals are to understand why the corona is so much hotter than the sun’s surface and to better understand coronal mass ejections.

These are huge eruptions of plasma from the sun into space that can cause satellites to malfunction and create power disruptions on Earth.

They’ll also conduct experiments to better understand how to fly satellites in high-precision formations.

ESA expects the first results from the study to be available this March.

Have more questions? Want to tell us how we’re doing? Use the “send us feedback” link below. ⬇️⬇️⬇️

With files from The Associated Press