Alberta’s revised restrictions on books in schools take aim at works containing explicit images of sexual acts, but it’s not the first time the province has banned graphics in the name of protecting children.

In 1954, the province established the Advisory Board on Objectionable Publications to control the sale of comic books and magazines.

The board was developed in response to a “growing outcry from parents, educators, religious leaders and others,” to investigate so-called “crime comics” that supposedly inspired undesirable behaviour in kids.

In July of this year, the provincial government issued a ministerial order asking school employees to remove library materials that depict sexual acts, including those contained in a “written passage.” That prompted Edmonton Public Schools to assemble a list of 226 books to remove from shelves and classrooms, including well-known works such as The Handmaid’s Tale, The Color Purple and The Godfather.

The uproar over the school board’s list forced the government to revise its ministerial order to remove “written passage” and add “visual depiction.”

While the subjects of these book bans seven decades apart differ in some ways, Carleton University historian Amie Wright said they also share some parallels, including the social conditions that can breed forms of censorship.

Wright, who researches the history of comic censorship in Canada as a PhD candidate and is the executive director of the Toronto Comic Arts Festival, said comic censorship falls under the study of “moral panic” — that is, a widespread, exaggerated and often irrational fear of something that is deemed a threat to society. Think rock music in the ’60s or video games in the early 2000s.

“Post-World War II, I think what a lot of us have forgotten is that there was so much anxiety,” she said, pointing to “societal disruptions” such as men returning to the workforce, women suddenly being moved out of it, and polio running rampant, especially among children.

“A lot of times, these moral panics, they really start to peak when you have several things colliding at once, so you have a lot of anxiety,” Wright said.

“And it’s very much in this similar climate of fear — I think of all of us coming out of the COVID pandemic — that comic censorship happened the last time.”

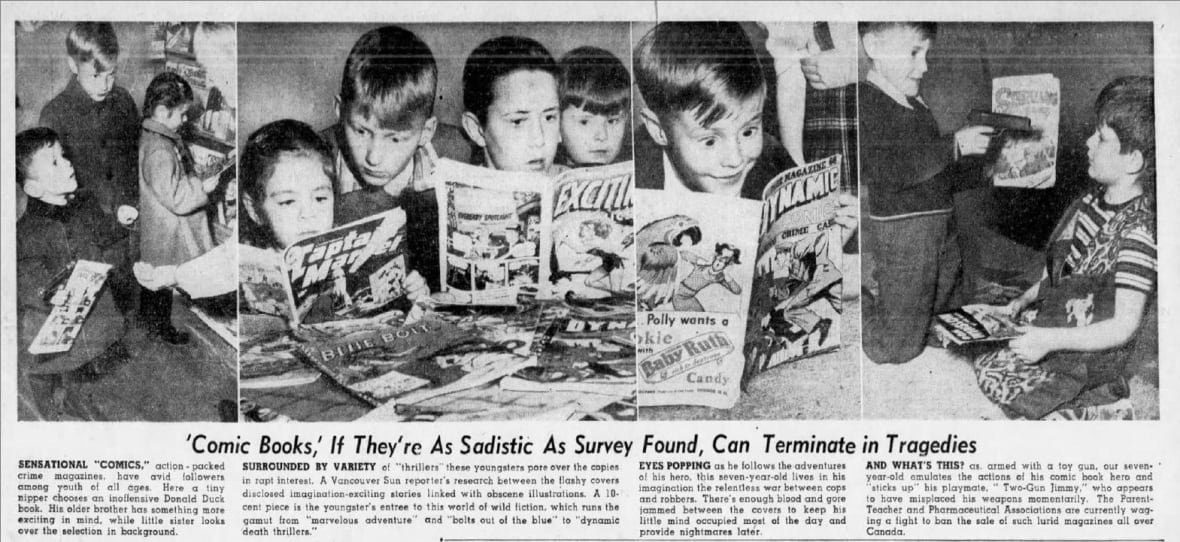

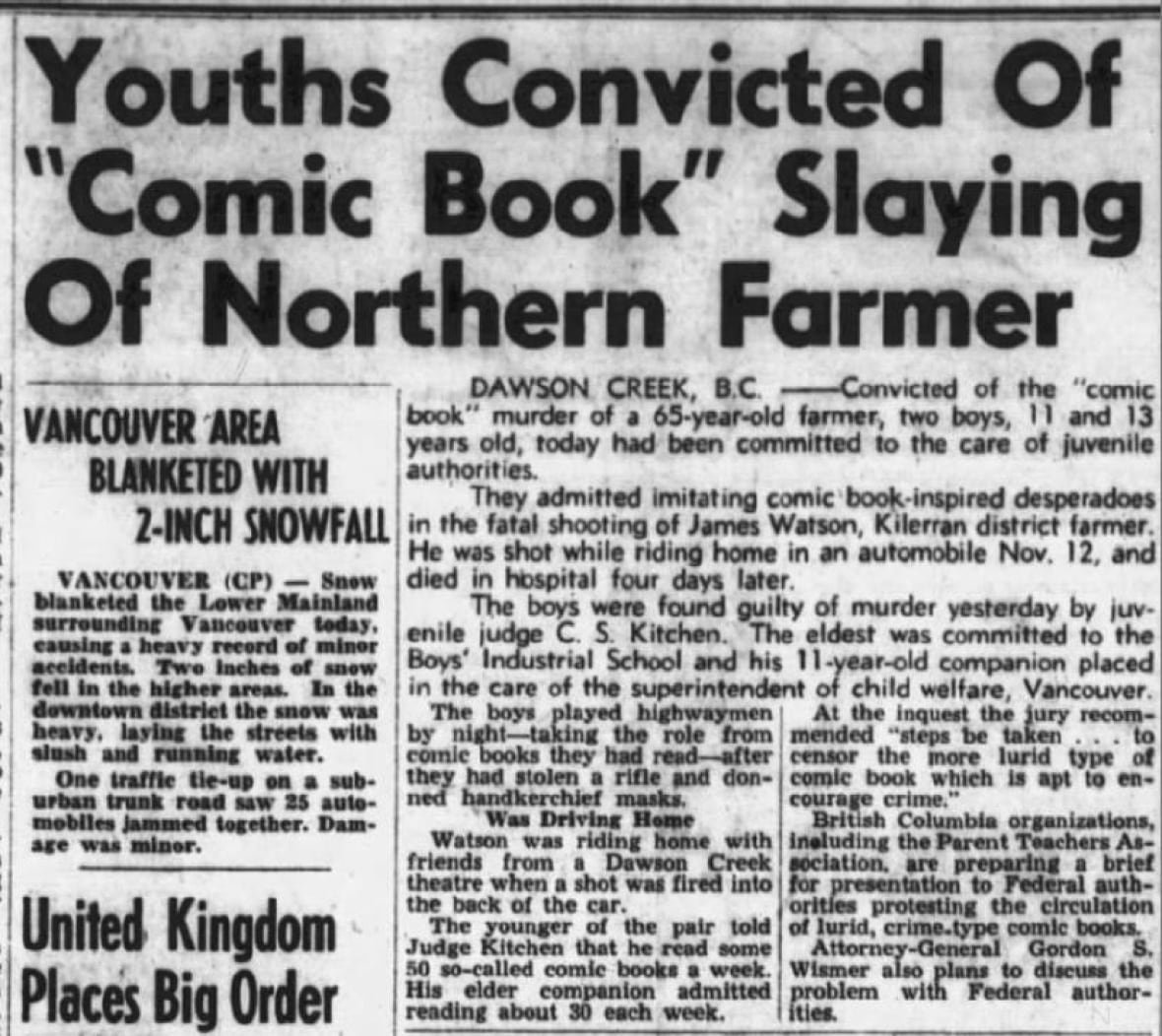

In November 1948, anxieties around the impact of comic books grew exponentially when two boys in Dawson Creek, B.C., were taking potshots with a rifle at vehicles passing by when they fatally struck a driver.

The story made national and international headlines, pointing to one major culprit: comic books. A Time magazine story from 1948 described the boys as having “been reading 40 to 50 comic books a week, and apparently what they read they took to heart.

“One evening last month, they acted like characters in their comic strips.”

The Crown prosecutor in the case, A.W. McLellan, is reported to have declared he would like to “see a concerted effort to wipe out this weird and horrible literature with which children are filling their heads.”

The case was so widely known, American psychiatrist Fredric Wertham would go on to write about it in his 1954 title Seduction of the Innocent, a book that cemented him as a leading critic of comic books and further fuelled the moral panic already taking shape in Canada, according to Wright.

Comic book ‘battle’

Later that month, the Edmonton Home and School Council began a campaign against “sex and crime-type comics” with support from the British Columbia Parent Teachers’ Association and the Alberta Federation of Home and School Associations, according to an Edmonton Bulletin story.

It was around this time that a 10-year-old future prime minister, Brian Mulroney, delivered a “passionate” award-winning speech on the dangers of crime comics, according to John Bell’s book Invaders from the North: How Canada Conquered the Comic Book Universe.

In 1949, “crime comics” were added to the Canadian Criminal Code under the obscenity clause, where they remained until 2018.

“What’s important to note is that the comics that we’re talking about, they’re not all ‘crime comics.’ It was a phrase that was used very arbitrarily to pretty much indicate anything that folks found objectionably concerning,” said Wright.

“There was a lot of discussion similar to today and hand wringing about, like, what about children … reading these comic books?”

The Advisory Board on Objectionable Publications

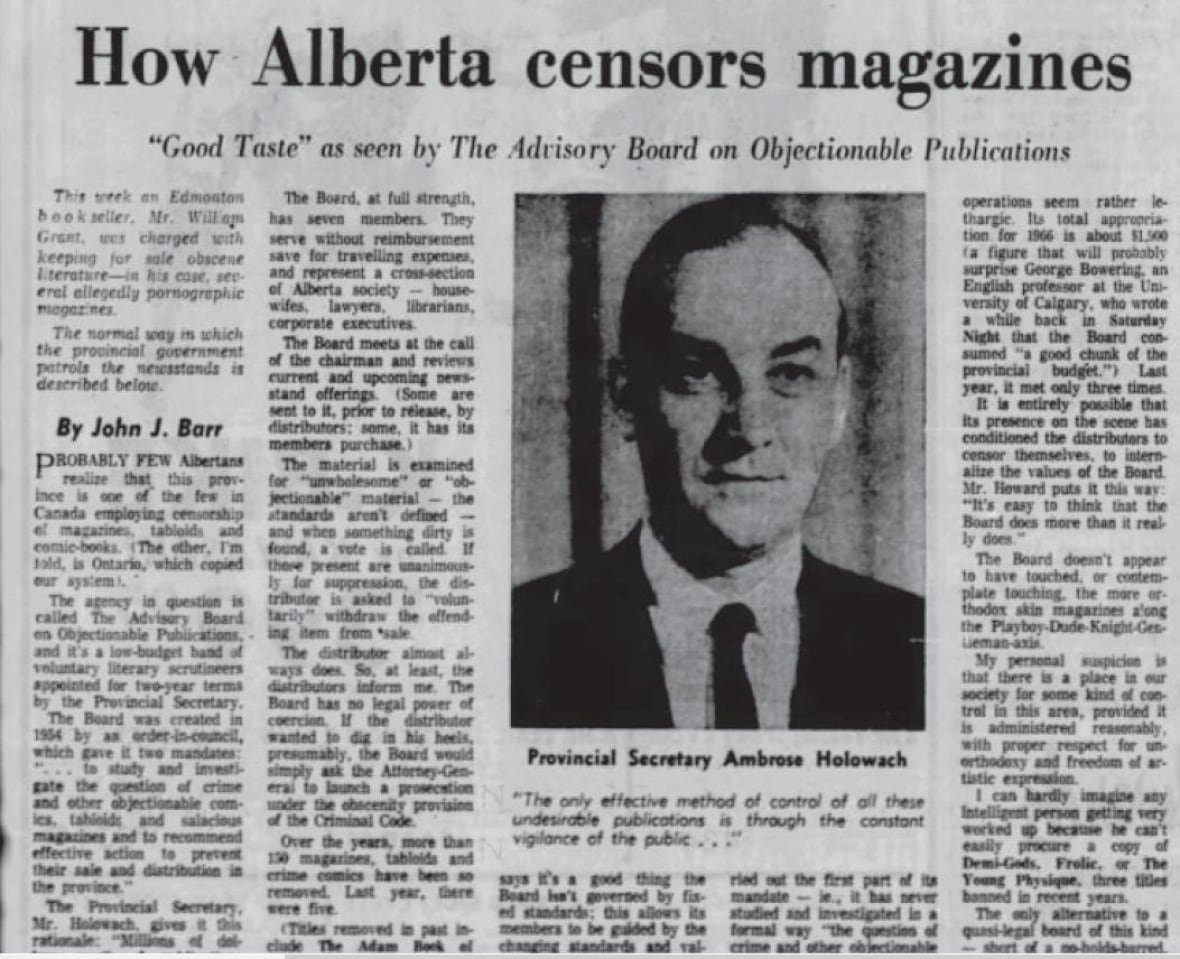

In 1954, Alberta’s Advisory Board on Objectionable Publications was born, comprised of seven members and chaired by a member of the Edmonton Public Library Board.

Working with parent, teacher and religious groups, along with arrangements with distributors and law enforcement, the board removed hundreds of titles from newsstands during its tenure.

According to Wright, there are few complete lists of the censored books. One from 1962 lists comic books including Amazing Detective and the romance comics My Love Secret and My Story. Notably, a number of adult periodicals also made the list, including men’s magazines Ace: The Magazine for Men of Distinction and Men’s Digest, and tabloids Hush-Hush and Top Secret.

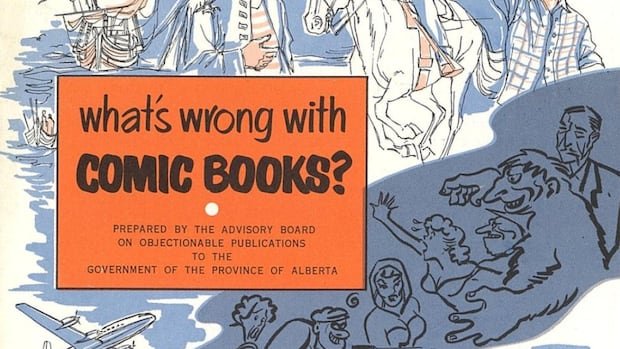

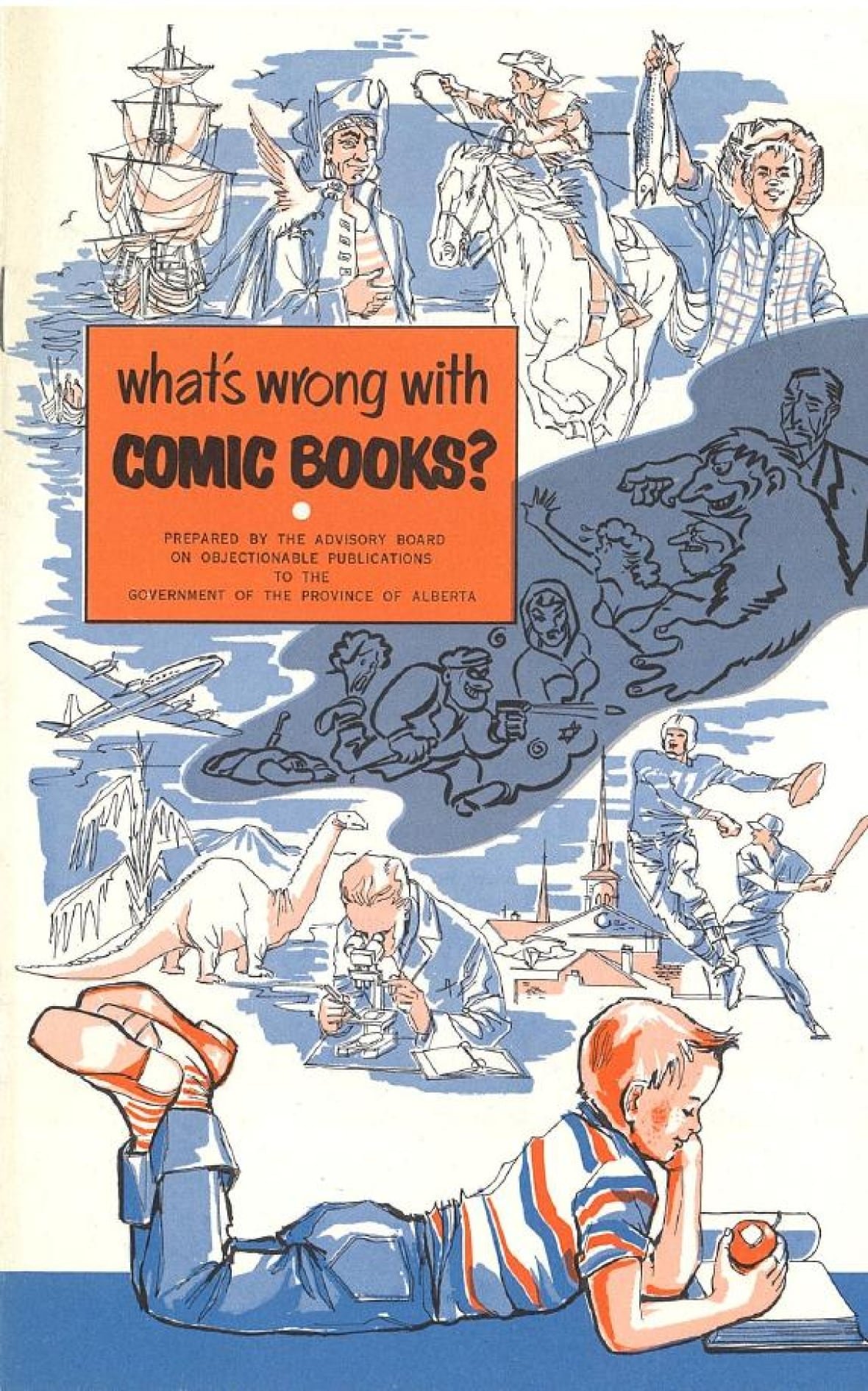

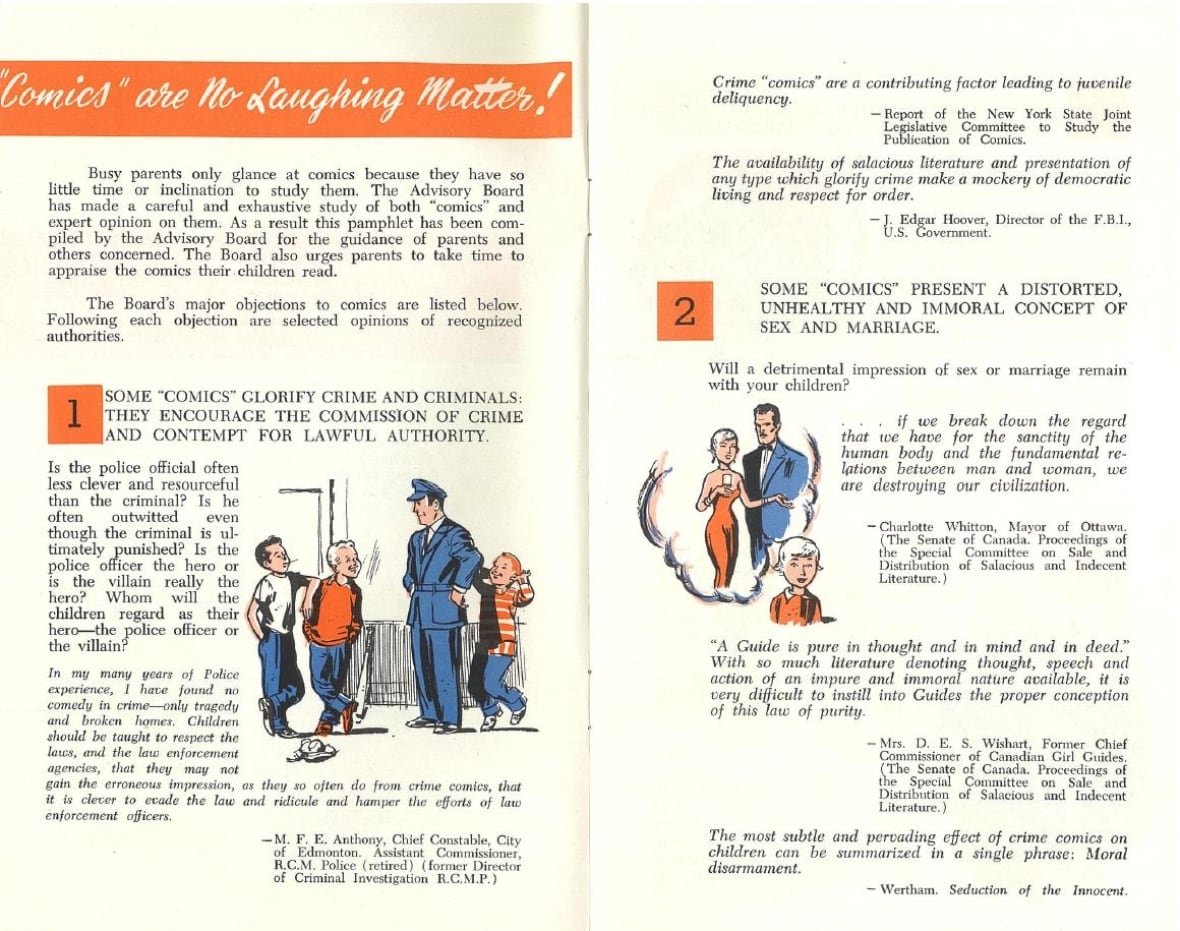

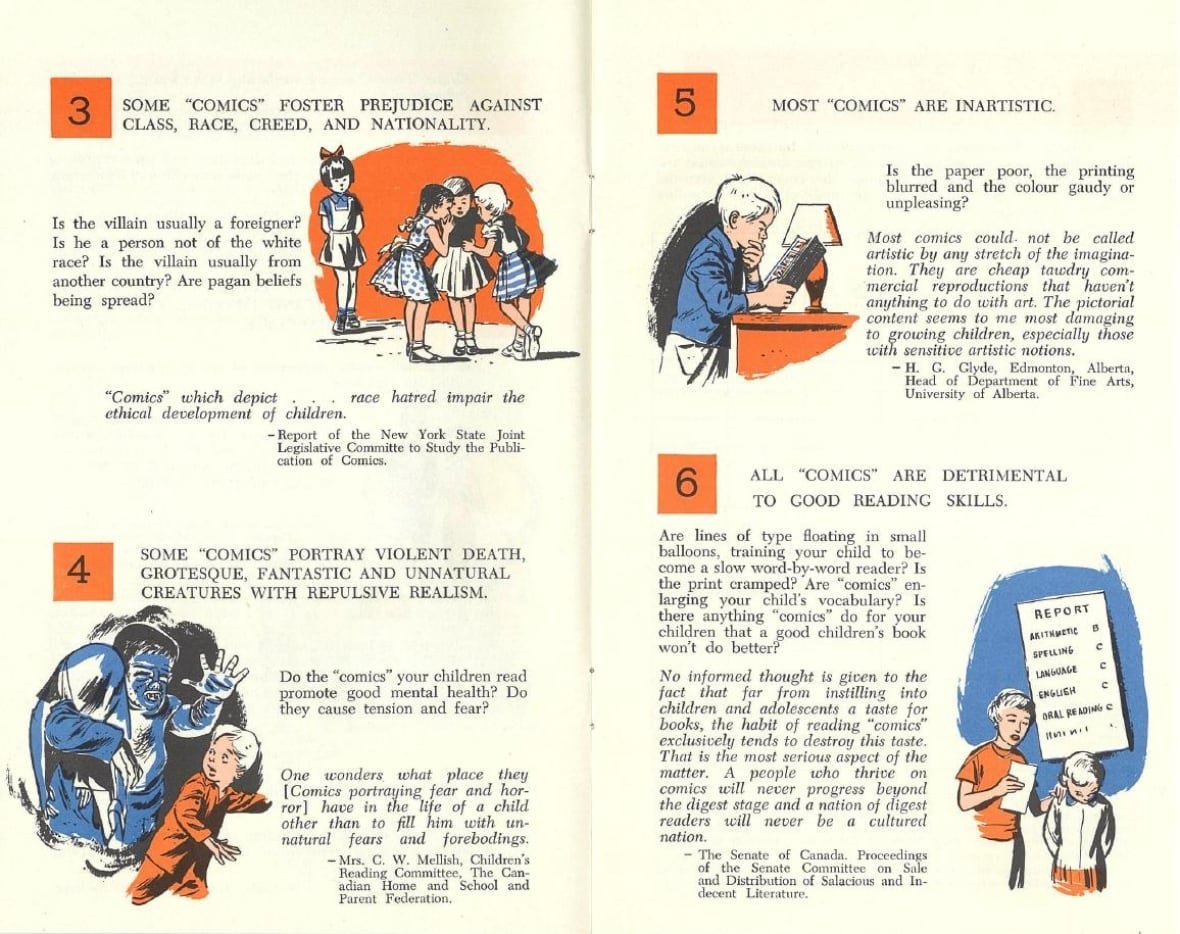

Two years after the board was established, it released a pamphlet called What’s Wrong with Comic Books? to “investigate the question of crime and other objectionable comics and salacious magazines” and to “prevent their sale and distribution.”

More than 40,000 copies of the pamphlet were distributed to schools, libraries and other organizations throughout Alberta and across North America, said Wright.

The board’s list of major objections included comics that “glorify crime and criminals,” ones that present a “distorted, unhealthy and immoral concept of sex and marriage,” and comics that “foster prejudice against class, race, creed, and nationality.”

“What the board talks a lot about is this idea of what’s ‘good’ and what’s ‘bad’ reading. So, this idea of: what is harmful to children?” said Wright.

“They used this platform of restricting comics because of the fear that it would be harmful to children and then used those powers to really create more broad newsstand monitoring across the whole province until the early 1970s.”

Twenty to 25 per cent of all periodicals, including Playboy and Rolling Stone, were removed in the years the board was active, according to Wright.

John J. Barr wrote in a May 1966 issue of the Edmonton Journal: “It is entirely possible that [the board’s] presence on the scene has conditioned the distributors to censor themselves, to internalize the values of the board.”

Wright said the board was actively corresponding with the federal government, other provincial governments and the RCMP, exerting influence across Canada and “normalizing certain ideas of censorship as protection.”

But public opinion of the board waned over two decades. According to Wright, “by the early 1970s, the public appetite was not there for this kind of oversight.”

In 1970, Edmonton Journal reporter Barry Craig spent several days studying the practice of censorship in the city. Writing about his research, Craig concluded that “in the end, censorship appears silly.

“The Edmonton police, the Alberta government … and the Objectionable Publications Board are all trying to keep men’s minds pure by limiting what they can see in a magazine or read in a book. It is like Don Quixote and his windmills.”

The Advisory Board on Objectionable Publications was officially dissolved in 1976 after about three years of being inactive.

Wright points out that historically, Albertans have pushed back. Fast forward to today, Alberta is again seeing governmental oversight in children’s reading material and, again, the move is unpopular with many.

“A lot of people talk about the censorship of the 1950s as being something that somehow was accepted by people and it was part of a norm. I don’t think that that was as true as people say,” Wright said.

“One of the things I found in newspaper articles was how much pushback was happening in Calgary, in Edmonton, in Lethbridge, from citizens writing in and saying, ‘Why does the board have the right to decide? You know, we should have the right to decide what our children read.'”