The hunt is on for the thieves who stole jewels from the Louvre on the weekend, but already the warnings are out that the items may never be seen again.

On Sunday morning, four men drove a truck up to the famed Paris museum, extended a ladder to the second floor and broke in. Officials say the thieves knew what they were doing and what they wanted to steal. In roughly seven minutes, the men made off with irreplaceable items from French royal history.

Here’s what we know so far.

What was stolen

It’s especially stinging that the items stolen were French crown jewels — symbols of the French state and the history of the country.

All of them were in the Apollon Gallery of the Louvre, which is on the second floor. The long hallway-like room features a ceiling and walls that are lavishly decorated with paintings and gold.

Since 1887 the ornate room has housed what’s left of the French crown jewels, after most were sold off. The remaining jewels were the target of this weekend’s heist. Once the thieves broke in, they went straight for those particular display cases, officials say.

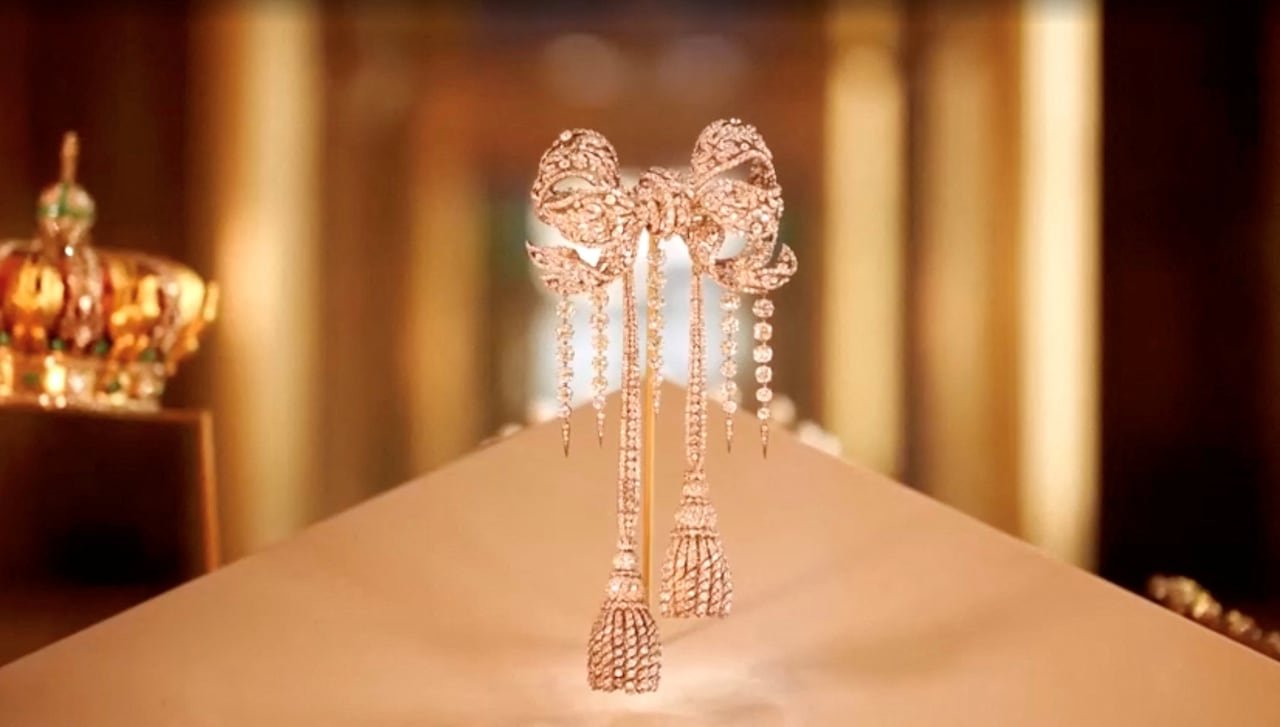

Eight objects were taken. Two diadems, one with sapphires — similar to a crown, a diadem is usually a jewelled headband or tiara that symbolizes the monarchy — a necklace and earrings that belonged to two 19th-century French queens; an emerald necklace and earrings that were held by Napoleon Bonaparte’s second wife; and two brooches, one of which was Empress Eugénie’s, Napoleon III’s wife.

One other object of Empress Eugénie’s was also stolen, but the thieves seem to have dropped it, as it was found broken outside the museum after the break-in. It was her emerald-set imperial crown, which contains more than 1,300 diamonds.

What’s the value of this stuff?

Since the heist was first reported, the items stolen have been described as “priceless,” in that their significance means they cannot be replaced for any amount of money.

Because these one-of-a-kind pieces would be instantly recognizable to virtually any interested buyer, it’s unlikely they could be sold as is. Far more likely is that they will be broken into pieces. Precious metal can be melted down, erasing knowledge of its origin. Valuable stones such as diamonds can be removed from the item and recut, making it difficult or impossible to detect where they came from.

However they’re sold, there are so far no reliable estimates on how much money the thieves might be able to get.

This has happened before

High-profile thievery from museums and art galleries has always happened, and it’s fodder for everything from news headlines to true crime books, Netflix shows and Hollywood movies.

The biggest heist in the history of the Louvre was when the most famous painting in the world was stolen. In 1911, a man named Vincenzo Peruggia took the Mona Lisa from its frame, and it disappeared for two years until it was recovered in Florence.

A big, relatively recent robbery was of a Canadian object. In 2017, a 100-kilogram solid gold coin known as the “Big Maple Leaf” was taken from a Berlin museum . The coin was worth around $6 million. It’s believed it was cut up and the pieces sold. Three men were later convicted.

What’s been described as the biggest art heist in U.S. history — and possibly the world — remains unsolved and the art is still missing. In 1990, two men disguised as police entered Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum and stole 13 artworks, including masterpieces by Rembrandt, Vermeer, Degas and Manet. The investigation was the subject of a documentary in 2021 called This Is a Robbery.

What’s being done?

The hunt is on for the Louvre thieves and the investigation is being done by a specialist police unit in Paris that has solved high-profile robberies before.

French government ministers asked senior officials across France “to immediately assess the existing security measures already in place around cultural institutions, and to strengthen them if necessary.”

“For too long we have looked into the security of visitors but not the security of artworks,” Culture Minister Rachida Dati said, adding that she wants to speed up plans to enhance security in French museums.

Museums around the world routinely complain they don’t have enough money to improve security. Christopher Marinello, the founder of Art Recovery International, an organization that tries to find stolen art, said the Louvre heist will put every institution on notice. “The Louvre is one of the most well funded museums in the world. And if they’re going to be hit, every museum is vulnerable.”