Director Timeea Mohamed Ahmed did not know exactly the kind of movie he was making when he signed on to Khartoum.

He knew the documentary, which had its sold-out Canadian premiere at Toronto’s Hot Docs Festival, would focus on his native Sudan. He knew it would bring together multiple directors from the country to tell their stories.

But what the crew couldn’t know was how a sudden war in Sudan would make it almost impossible to craft the film, and eventually, impossible to stay there to finish it. In 2023, the team was forced to flee to parts of East Africa, where they finished the film through creative tools like green screens and animation, having their subjects re-enact scenarios that weren’t possible to film in person.

And given the recent wars that have broken out across the world, Ahmed is far from alone. He’s part of a cohort of filmmakers at this year’s festival, whose work is highlighted under the “Made in Exile” banner.

The new category is co-sponsored by the PEN Canada non-profit, and highlights stories of war and crisis in artists’ homelands that they’ve had to leave.

Despite the tragedy inherent to the category, Ahmed and other filmmakers see within its scope surprising signs of hope. The films highlight their creators’ unique strategies, as well as the collaboration inspired by their obstacles. That, he said, is a heartening boon for a medium already on the ropes.

“This film has a Palestinian editor, Italian producer — it has so much [more] people than I thought possible, from different countries and nationalities and languages,” Ahmed said of Khartoum.

“It showed me that exile can be also an advantage more than it’s a disadvantage.”

Following a year of financial uncertainty and challenges the Hot Docs Canadian International Film Festival will be returning at the end of April. The festival’s lineup includes 113 films from 47 countries. CBC’s Talia Ricci has the story.

Category came partly from financial troubles

According to Hot Docs’ programming director Heather Haynes, the opportunity came about partly from the organization’s very public financial woes. As the festival employed some “right-sizing” techniques — dropping its total film count down from 214 in 2023 to 113 films in 2025 — updating the Made In program to cover artists from more than one country or region also seemed like a timely change. (The category typically highlights a specific country’s work under the “Made in” format.)

The team had wanted to try the project out for the last three years, she said. But the state of the world in 2025 made it a particularly urgent year for testing.

One of the affected filmmakers was Areeb Zuaiter, the Palestinian director of the 2024 sold-out Hot Docs film Yalla Parkour. She made that documentary, which follows a young parkour athlete attempting to emigrate from Gaza, over the course of 10 years.

The film was created in advance of Hamas’s attack on Israel — and Israel’s subsequent war — and is billed as a last glimpse of a pre-Oct. 7 Gaza. But Zuaiter’s personal sense of exile from a Palestinian state predates the war: Though she was born in Nablus in the West Bank, she and her parents left when she was an infant. Along with annual trips back to Nablus, they made a one-time visit to Gaza, where the memory of her mother’s smile by the seaside made a particular impression on her.

Meeting the young parkour athlete coloured Zuaiter’s personal connection to the territory, and she observes that his desire to leave the territory triggers her own guilt for having left so many years ago.

And as the war intensified, so did her project’s theme.

“My full attention was [in] showing … the conditions in Gaza, how [Gazans] have this spirit that I eventually ended up calling the Palestinian spirit, that reminded me of my mom,” she said.

“But then when everything happened lately, we felt this sense of [urgency] that we need to finish this film. And at the same time, we will be insensitive if we don’t address what’s going on.”

Shame, trauma and hope

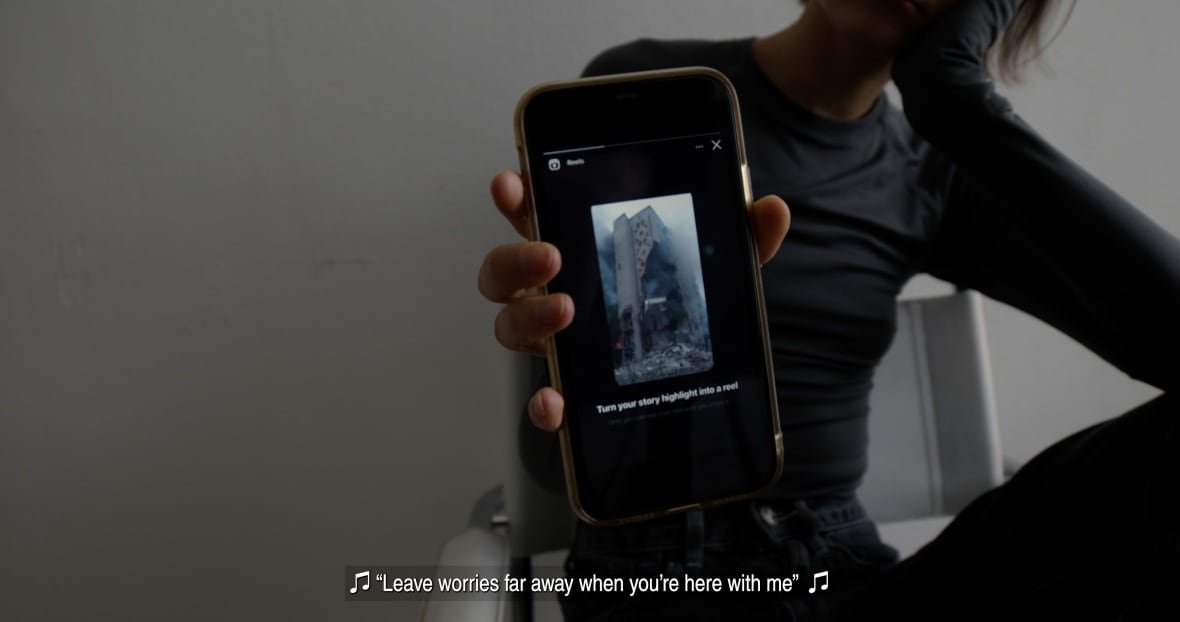

That impulse also coloured the creation of The Longer You Bleed, another entry. It looks at the endless stream of violent footage from Russia’s war in Ukraine shared on social media, and the toll it takes on young Ukrainians.

The idea first came from Liubov Dyvak’s phone. Dyvak, the film’s Ukrainian producer and subject, made the doc with her partner and director, Ewan Waddell.

Dyvak is currently based in Germany, and like many Ukrainians, she uses her phone for activism, Waddell said, and saves images she’s seen online and from friends. But she found that the phone, as part of its settings, would automatically generate collages of images she’d downloaded, pairing them with bubbly pop music. Just before they started work on what would become the film, her phone made another one: a montage of destroyed buildings, rubble and civilians without legs.

Though she was physically in a safe space, at the same time she felt constantly traumatized by social media, she said: “I noticed this kind of guilt of survival … and shame. And not being able to share your experience because it feels [like] people from your country experience, also, physical danger. Which is much more intense.”

Liubov said it reinforced both the horror of the war, and the separation she had from her friends in other parts of Europe — people who largely used social media innocently, and without encountering as much graphic violence as she did. It also made her wonder about her connection to other Ukrainians, given her experience of being in a sort of exile — of not being physically in her home, but seeing her friends’ experiences second-hand through their shared images.

But working on the documentary itself helped to alleviate some of that guilt. Talking to other Ukrainians in her situation — similarly removed from their home country during the war — made her feel more connected, not less.

“It was very precious to be able to express and kind of investigate all these feelings,” she said. “It gave me these feelings that I’m not alone in this…. This feeling of unity, which is, I think, very, very crucial for mental sanity and for survival.”